Written by Mr. Dasmani Laary, Eastern Regional Head, Ghana News Agency

Introduction

In Ghana, internal migration has long served as a vital livelihood strategy, particularly for young people moving from the northern regions to urban centres in the south. Yet a new and puzzling trend has begun to take shape. Entirely lawful movements are increasingly being framed as “irregular.” This emerging narrative is striking because Ghana’s constitution guarantees freedom of movement for all citizens. Why, then, are certain internal movements being reframed in this way? The issue appears to extend beyond legality. Institutions and community actors often raise concerns about risk, hardship, vulnerability and moral behaviour. Such interpretations blur the boundary between dangerous and illegal migration. Consequently, they create a category that migrants themselves rarely recognise.

Central to this discussion is the concept of “Irregularisation Across Scales: From International to Internal Irregular Migration in Ghana.” This topic was deeply explored in a keynote lecture delivered by Prof. Leander Kandilige of the University of Ghana and Dr. Cathrine Talleraas of CMI, Norway, at the 2025 International Migrants Day virtual event in Ghana. Their analysis illustrates how global narratives, donor agendas, institutional practices and community perspectives interact to construct internal mobility as problematic. Drawing on their analysis, this article examines the growing irregularisation of internal migration in Ghana. How legal, everyday movement becomes problematised, and what this means for mobility governance and the rights of internal migrants. It scrutinises the concept of “irregularisation”: the process through which internal migrants are framed as irregular, not because they break laws, but because of how their movements are perceived.

Global Language, Local Effects

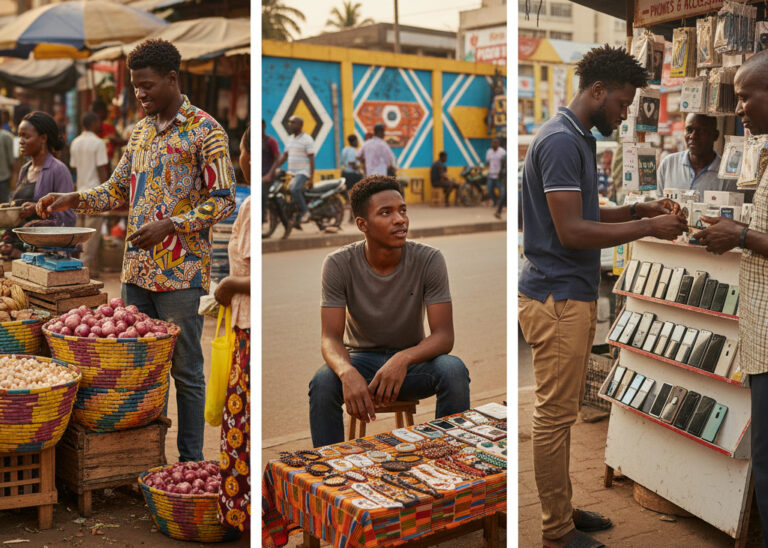

As Kandilige and Talleraas (2025) emphasise, global policy frameworks such as the Global Compact for Migration and the Sustainable Development Goals were originally designed to address cross-border mobility, not internal migration. Yet these frameworks are increasingly shaping how internal movement is discussed in Ghana. Their influence is evident in national policies and public discourse, where internal migration is now often framed through lenses of risk, illegality, and protection. Movements once seen as routine, especially by young migrants from northern Ghana, are now portrayed as dangerous or morally suspect. As these global narratives filter down, local actors adapt and reinterpret them. The term “irregular”, for instance, is now used beyond its legal meaning to express concerns about hazard, morality, or social order, even when no laws are broken. However, Kandilige and Talleraas note that community members rarely use such terms. Instead, they speak of “hardship”, “uncertainty”, and “vulnerability”, particularly in relation to kayayei. These women describe their journeys simply as “travelling to work”, highlighting economic necessity rather than deviance. This contrast reveals a growing disconnect between institutional language and lived experience, raising concerns about how global frameworks may obscure the structural realities driving internal migration.

How Labels Gain Power

Drawing on Bowker, Star, and Hacking, the lecture underscores that categorisation is never neutral. Labels shape what authorities see, regulate, and act upon, gaining meaning through routine administrative practices. Terms like “refugee” or “irregular” may appear objective, but research shows they are socially constructed, shaped by political and moral judgments embedded in bureaucracy.

In Ghana, this is evident in how “irregular” is applied to internal migrants, particularly young women working as kayayei, despite their movements being entirely legal. As global migration labels filter into national and local contexts, their meanings shift. Frontline actors, such as immigration officials and civil society workers, adapt these terms into governance tools, turning implementation sites into arenas where categories are constantly negotiated.

Kandilige and Talleraas provide robust evidence for these dynamics. Drawing on eighty-five interviews, two focus groups, and data from the MIGNEX and EFFEXT projects, their study spans multiple regions and institutions. It reveals divergent interpretations: state actors often associate irregularity with criminality; CSOs focus on vulnerability and protection; while community members emphasise opportunity and legality, rarely using the term “irregular.” As these perspectives converge, the notion of danger increasingly replaces legal definitions, reinforcing the irregularisation of internal mobility, even in the absence of any legal breach.

Mechanics of Irregularisation

The lecture illustrates how the concept of irregularisation is unfolding in practice. Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and state agencies have rebranded their campaigns to reflect shifting narratives. For instance, school-based “Anti-illegal Route to Europe Clubs” have been renamed “Anti-dangerous Migration Clubs,” now targeting internal migration alongside international routes. A CSO representative in Tamale explained, “Since we have added internal migration as one of the major problems facing the Northern Region, we rebranded the names.”

This rebranding is not merely symbolic. It reflects how global risk language is being repurposed to govern domestic mobility. Security practices have followed a similar path. Immigration officers have established inland checkpoints to intercept young migrants, particularly minors, moving to urban centres like Tamale for work. These actions are often framed as child protection or anti-trafficking efforts. Yet, they operate outside formal legal frameworks and risk infringing on constitutional rights. As one officer acknowledged, “We cannot prevent people from moving when they are moving on their own.” At checkpoints like Savelugu, presumed minors en route to Tamale for head portering are sometimes intercepted. However, officers admit they lack shelters or detention facilities, making enforcement difficult. While the stated aim is protection, the practice effectively functions as a form of mobility control.

Meanwhile, Migrant Information Centres and Migrant Resource Centres now advise on “irregular internal migration,” treating domestic and international movement as part of a single risk continuum. New terms such as “independent” and “voluntary” migration have entered institutional language. According to a CSO representative, as cited in the lecture, voluntary migration involves parental consent, while independent migration refers to youth travelling alone due to peer pressure or curiosity.

These classifications are not grounded in law. They gain authority through institutional discretion, donor influence, and prevailing moral narratives around youth mobility and kayayei. The lecture warns that such practices blur the line between support and surveillance, potentially undermining constitutional rights, especially when profiling based on age, gender, or presumed intent replaces legal standards.

Protection, Rights, and the Constitutional Paradox

Ghanaian officials acknowledge the constitutional right to internal mobility. A staff member at the Migrant Information Centre (MIC) in Tamale affirms, “With regards to internal migration and per our constitution, everyone has the right to move freely.” If a Ghanaian refuses to return after being intercepted, “we cannot tell the person to go back… we only show our concern.” This recognition, however, reveals a central paradox in the irregularisation of internal migration. While formal rights remain intact, practices shaped by global migration discourses can still constrain movement in subtle but significant ways. Travellers, especially young migrants, may be screened, questioned, or profiled based on perceived vulnerability or presumed future intentions. In this context, irregularity shifts from a legal status to a behavioural category. It is no longer defined strictly by law, but by institutional judgments about risk. As Kandilige and Talleraas argue, this marks the rise of pre-emptive governance, where mobility is managed not through legal violations, but through anticipatory control.

Drivers and Lived Realities

The lecture situates Ghana’s shifting migration governance within the real-life pressures that shape mobility decisions. For international migration, respondents cited unemployment, poverty, rising living costs, limited access to credit, rapid population growth, and climate-induced declines in agricultural productivity. Internal migration, by contrast, was linked to ethnic conflict, weak state support, perceived parental neglect, fear of witchcraft accusations, urban aspirations, and access to education. These drivers help explain why communities often focus on danger rather than illegality. Many young people move out of necessity, not choice. Head portering, for example, is both a survival strategy and a source of stigma, especially for girls and young women. The intersection of economic hardship and social anxiety makes communities more receptive to external narratives that conflate risk with irregularity, even as migrants themselves describe their actions simply as seeking work. These realities show that internal migration in Ghana is a rational response to structural inequalities, not a deviant or unlawful act.

Implications for Scholars and Policymakers

Kandilige and Talleraas argue that labels like “irregular” are not neutral descriptors but fluid tools of power. When global policy language is adopted without context, it can lead to exclusion and control rather than protection, especially for rural–urban labour migrants and low-skilled movers. For African mobility scholars, two lessons stand out. First, the focus should shift from the legality of movement to how categories are constructed and applied in practice. Second, migration governance must be assessed not only by its protective aims but also by its alignment with constitutional rights to free movement. Understanding irregularisation as a process, rather than a fixed status, reveals how inequality, institutional discretion, and shifting norms shape the everyday realities of mobility in Ghana.

Moving Forward

For internal migration to remain a vital livelihood strategy, policies must uphold Ghana’s constitutional right to free movement and reflect the lived realities of migrants. This requires recognising migrants not only as vulnerable, but also as agents navigating structural constraints. It also demands scrutiny of how donor priorities and institutional practices may unintentionally restrict freedoms. The lecture highlights that migration categories are not static. Community terms like “independent” and “voluntary” often rise into institutional language, are redefined, and return with regulatory weight. Ensuring that this circulation of labels promotes mobility justice, rather than administrative control, is critical. Kandilige and Talleraas caution that when risk replaces law as the dominant lens for interpreting movement, even legal mobility can be framed as irregular. Preventing this shift calls for vigilant research, thoughtful policy, and strong engagement with communities whose livelihoods depend on movement.

Call to Action

Scholars, practitioners, and policymakers must continue to interrogate how migration categories are constructed and applied. Viewing irregularity as a process, not a fixed status, helps challenge restrictive interpretations and supports more inclusive, rights-based governance. This approach is essential for building migration systems that are context-sensitive and socially just across Africa.

Conclusion

The Ghanaian case illustrates how global migration narratives can reshape local governance in ways that constrain internal mobility. The concept of irregularisation explains how lawful movement, long used for survival and opportunity, can be recast as risky or deviant. As international actors like IOM, ICMPD, and GIZ expand their influence, caution is warranted. Global labels must not override constitutional rights or community understandings of mobility. Policies must remain grounded in everyday realities and protect Ghanaians’ right to move with dignity, safety, and opportunity.

END!