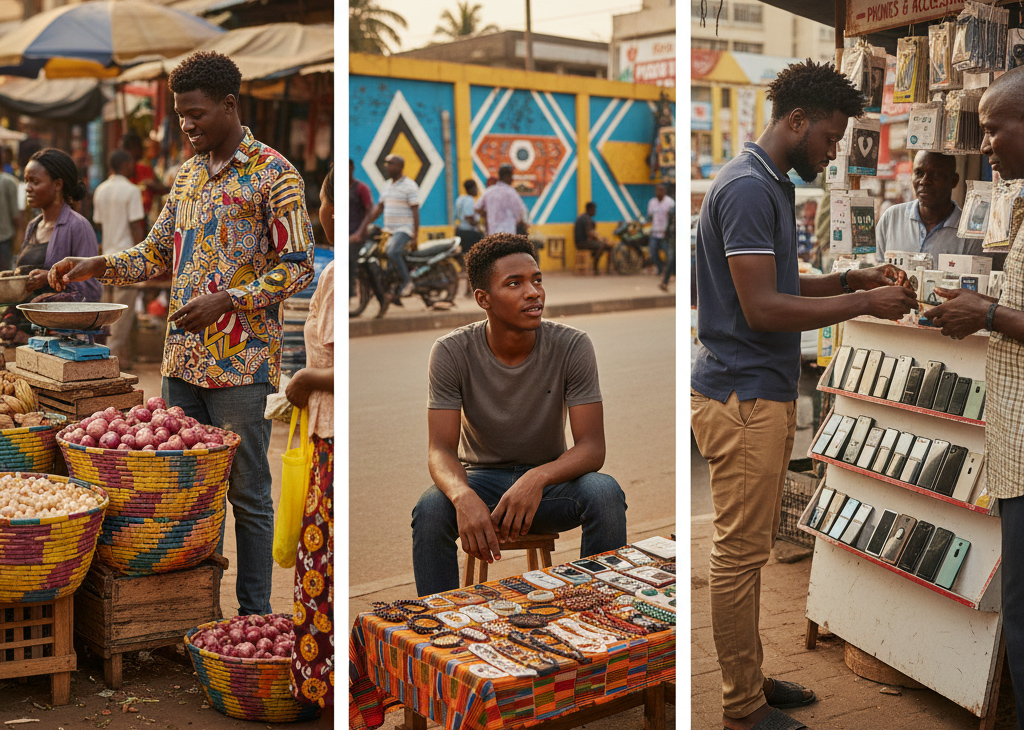

Three men: working, hoping, and building in Accra

By: Owusuaa Eshia (PhD): owusuaeshia@gmail.com

Every 18th December (International Migrants Day), the world takes a moment to honour migrants. On this day, the African Mobility Scholars Association (AMSA) made the decision to focus on the stories and messages of a few West African Migrants to avoid making big statements and instead hear from actual people who are making a living in the informal sector in Accra, Ghana. We join hands with everyone working within the migration space to highlight the contributions by migrants. The participants for this blog are workers in Accra’s everyday economy, who sell, serve clients and customers, pay dues, hire helpers, and keep markets moving. Their stories also reflect what research in Ghana keeps revealing, which consistently shows that a large number of migrants find employment in the informal economy and make contributions through service provision, trading, and daily spending (OECD/ILO, 2018). Three West African economic migrants, Mamoudou, Emmanuel, and Abdou from Guinea, Nigeria and Niger, respectively, who reside in Ghana, share their personal stories on this blog.

Mamoudou: The Make-up and Jewellery Seller

Mamoudou, 35, is from a village in Boke in Guinea. Here in the Greater Accra Region, he resides in Amasaman. I’ve spent the last four years in Ghana. I ride a trotro to Osu every morning, where I sell make-up and jewellery by the side of the road and occasionally in front of stores. Mamoudou begins by discussing how he left his village to support his family because the opportunity he desired was unavailable there. After completing basic education, he assisted his father on the farm, where they cultivated cassava, corn, and groundnuts. He chose Ghana in part because of the country’s peace, the fact that he didn’t need a passport to enter Ghana, and the fact that he followed friends who came to Ghana to work.

Mamoudou sells cosmetics (face powder, lipstick, lip gloss) and jewellery (earrings, bangles and chains) in Osu, a suburb of Accra. He believes he would have the life he desired if he lived in Ghana. He says there are opportunities in Ghana, but they require hard work. Sales may be slow on some days, he explained, but it’s better than doing nothing. The same mix is seen in research on migrant trading and street livelihoods in Accra: people come for opportunities, but they also deal with insecurity and daily pressure to survive (Wrigley-Asante, 2014).

Despite this, Mamoudou believes Ghana allows him to live a decent life and support his family back home. He stated that he purchases his goods from the local market and pays his daily toll when asked how he contributes to Ghana’s economy. Mamoudou also added that he contributes to the growth of other businesses by spending the majority of his earnings domestically.

Emmanuel: The Mobile Phone Accessory Vendor

Emmanuel is the name of another immigrant I spoke with. Emmanuel, a 32-year-old Nigerian immigrant, shares a room with other men in Osu. It has been five years since Emmanuel arrived. He claims that he likes Ghana, that the country is peaceful, and that he feels secure here. In crowded areas with constant foot traffic, he sells mobile phone accessories like screen protectors, chargers and earphones. I met him in the Cantonments, where he had packed his trolley and was waiting for customers. According to him, to serve his customers, he moves around to where they are. This is consistent with the findings of Oteng-Ababio and van der Velden’s urban research in Accra, where people establish their own systems of sales, repair, supply links, and customer networks and informal mobile phone markets have expanded due to high demand (Oteng-Ababio & van der Velden, 2020).

When asked if he believes Ghana offers opportunities. Emmanuel hesitated a moment before responding, “Yes.” He says the opportunity is there, but his line of work requires more capital, reliable suppliers, connections, and staying out of trouble. On the challenging side, research on West African immigrant entrepreneurs in Accra reveals health risks, housing issues, working long hours under the sun and depending on social networks for support. (Yendaw et al, 2023).

When questioned about how he contributes to Ghana’s economy, Emmanuel mentioned that and I quote: “my line of work supports the communication needs of the citizens of Ghana. I offer reasonably priced options to people with little money. I also pay my taxes and pay rent to my landlord. All these helps support the economy”. He finally revealed that he is teaching one apprentice in the mobile accessory business. Even though it is not accurately recorded in official records, informal work supports households and local expenditure in this way (OECD/ILO, 2018).

Abdou: The Onion Trader

Abdou was the last immigrant I engaged for this blog. He is from Maradi, Niger and is 45 years old. He has spent nearly a decade in Ghana. Back home in Maradi, he was a farmer who cultivated millet, onions, and a few vegetables. He currently makes a living by selling onions at Tudu in Accra. He claims that he travelled to Ghana because trading seemed like a quicker way to make money and provide for his family. After all, farming back home was unprofitable and caused financial difficulty.

Abdou sees opportunity in Ghana because people visit the market daily, chop bars buy, restaurants buy, and households cook every day. However, he also said that his business is affected by the seasonal fluctuations of onion prices, poor storage losses and lack of a permanent location in the market. Asiedu and Agyei-Mensah’s (2008) research on street trading and market livelihoods in Accra demonstrates how vendors may experience harassment and insecurity, even as they provide essential services in the city.

Abdou mentioned that he makes a variety of contributions to Ghana’s economy. According to him, he hires head porters to transport his onions, supports food supply, pays AMA daily tax, and purchases food and other goods from other vendors. His expenditure support the growth of other businesses.

What they give back to Ghana’s economy

All three migrants: Mamoudou, Emmanuel and Abdou, said that while there are opportunities for migrants in Ghana’s informal economy, securing a steady growth in any endeavour requires hard work. Even though it is not documented in policy speeches, all three West African migrants make contributions that many people are aware of. They fill gaps in providing goods and services to the Ghanaian people (phone accessories, make-up items and onion supply). Again, they also spend their earnings locally to pay rent, buy food and other goods and services. They pay taxesFinally, they generate minor jobs for others, such as drivers, head porters, apprentices and loaders.

Closing Thought for 18th December

The message of Mamoudou, Emmanuel and Abdou on this International Migrants’ Day is straightforward and uncomplicated. We came to Ghana to work, we are working, and we hope to keep doing so in peace. The three serves as a reminder that migration is not just about moving, but it also has everything to do with employment, the daily struggle to survive, the expansion of business, and contributing. They came to Ghana in search of an opportunity, and they stayed because they built a customer base. One earring, one phone charger, one onion at a time, their labour is woven into Accra’s economy whether or not their efforts are acknowledged.

References

Adepoju, A. (2002). Fostering free movement of persons in West Africa: Achievements, constraints, and prospects for international migration. International Migration, 40(2), 3–28. (

Asiedu, A. B., & Agyei-Mensah, S. (2008). Traders on the run: Activities of street vendors in the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography.

DAI (in association with Nathan Associates London Ltd.). (2014). Onion Market Diagnostics Report: DFID Market Development (MADE) in Northern Ghana Programme (February 2014).

OECD & ILO. (2018). How immigrants contribute to Ghana’s economy. OECD Publishing.

Oteng-Ababio, M., & van der Velden, M. (2021). Connectivity in chaotic urban spaces: Mapping informal mobile phone market clusters in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(6), 1178–1195.

Wrigley-Asante, C. (2014). Accra turns lives around: Female migrant traders and their empowerment experiences in Accra, Ghana. Géneros: Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 3(2), 341–367.

Yeboah, T., Kandilige, L., Bisong, A., Garba, F., & Teye, J. K. (2021). The ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol and diversity of experiences of different categories of migrants: A qualitative study. International Migration, 59(3), 228–244.

Yendaw, E., Baatiema, L., & Ameyaw, E. K. (2023). Perceived risks, challenges and coping strategies among West African immigrant entrepreneurs in Ghana. Heliyon, 9(11), e21279.